A very important woman in my life passed away this week. I haven’t blogged in a while for many reasons, but mostly because I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write about. But today, I knew – I wanted to write about Ms. Glenda, my mentor, my friend, my second mother.

Glenda Brown was a force. A beautiful Texas woman who was taught to be a lady by her mother and Miss Eloise of the Beaumont Melody Maids, she was often underestimated by those who thought that what they saw on the outside – big blond curls, false eyelashes, lipstick outlining her mega-watt smile – was all she was.

But Ms. Glenda was smart and savvy. She had vision and grit. She was warm and loving, but she also knew how to establish boundaries – “No, we’re not doing that,” she would say, shaking her index finger with its prettily painted nail at whomever had crossed the line, be it a small child in a ballet class or a colleague in a meeting.

I first met Ms. Glenda when I was 13, in the fall of 1980. She and two other representatives of what was then the Southwestern Regional Ballet Association (now Regional Dance America/Southwest) traveled to Clinton, Oklahoma to evaluate our pre-professional company for admittance into the organization. Glenda made a definite impression on me – I remember her smile and how kind she seemed when she told us we’d been accepted as an intern company. After that, I would see her from afar at the annual Festivals I attended as a dancer; little did I know then how much she would come to impact my life, both through our dance connection and beyond.

In 1987, the National Association of Regional Ballet folded, closing its office in New York City and leaving its five member regions without a central governing organization. Glenda and four other visionaries, including her co-director at Allegro Ballet of Houston, Peggy Girouard, formed Regional Dance America in 1988 to provide a national umbrella to connect and unify the regions and to save the primary national project of NARB, the Craft of Choreography Conference (now the National Choreography Intensive). These five ladies – Glenda, Peggy, Lila Zali, Barbara Crockett, and Cassandra Crowley – took on additional leadership roles beyond those they already had within the pre-professional companies and schools they directed. Glenda herself took the helm of the Choreography Conference for over a decade, overseeing the two-week workshop that brought choreographers and dancers together to explore and create choreography under the tutelage of noted choreographers, music directors, and dance teachers. Eventually, Glenda also became the national board’s President and spearheaded the first-ever National Festival, a week-long extravaganza that brought 100 member companies to Houston in 1997 for classes and performances.

I became a studio owner and the artistic director of Western Oklahoma Ballet Theatre in 1988, when I was only 20 years old. WOBT was by then a performing company in what was becoming RDA/SW. Ms. Glenda, who was the presiding officer of the Southwest region at the time, welcomed me to my new role and helped me navigate within the region as a director rather than a dancer. She taught me about the business side of the organization and in 1991, because of her support, I was elected Secretary of RDA/SW, a leadership position I held for several years before the board enacted term limits. I later served as President from 2008-2011, which I could not have done successfully without Glenda’s example and encouragement.

Ms. Glenda helped me with the artistic side of things, as well. She recommended teachers and choreographers to work with my company. And she encouraged me, as a novice choreographer, to attend the Choreography Conference. Though initially I was very anxious – so much so that I went as an observer before I summoned the courage to go as a choreographer – those two weeks became an annual event for me for several years. I came to relish the time to focus on just being creative, instead of on the million other things I had to think about while running a school and a performing company. And Glenda always put together an amazing faculty, knowledgeable and generous. I soaked everything in like a sponge, and grew in skill and confidence to become an award-winning choreographer. In addition to intense work, it was also a lot of fun, and where I truly got to know Ms. Glenda – eating meals together in the cafeteria or staying up late and chatting about dance…and everything else under the sun.

That was one of Ms. Glenda’s special gifts, making all sorts of occasions, even everyday ones, fun and memorable. In 1995, she and her daughter Vanessa invited me to go on a trip to Destin, Florida with them. An avid traveler, this was one of Glenda’s favorite places – the white sand, the clear water, the memories of camping there when her kids were growing up. I was very excited about seeing Destin, though I was somewhat dreading the long car ride from Houston. However, as always with Glenda, it was an adventure. We veered off I-10 somewhere in East Texas because she saw a sign for homemade tamales that we just had to try. We also got drive-through samples of margaritas, because that was legal (!?!) in Louisiana. We detoured into New Orleans to have red beans and rice with one of her friends. At every stop, she would say “Park it in the shade, daughter!” (something her dad always said to her when she started driving; it has since become a saying in my family too). We sang Frank Sinatra songs, talked, and laughed and laughed – Vanessa, very much like Glenda in many ways, is one of the funniest humans I know. And once we arrived in Destin, the fun continued. Ms. Glenda had us drink apple cider vinegar with honey each morning, because that was her current health potion…but we also had beer for the beach. We got up early to enjoy the sand before it was too hot, and then would go for lunch and a nap or a quick shopping/sightseeing excursion, and then go out to the beach again in the evening before staying up late watching movies and talking and laughing. I remember her serenading us one morning while we drank our apple cider vinegar on the patio. She was in her swimsuit and sarong, and sang a song from her time touring the world with the Melody Maids, complete with all the dance moves, including a lovely hula. This was over 25 years ago, and these memories are clear and delightful, not because anything super exciting or special happened, but because Glenda had such joy for life, an attitude that something fun or wonderful was just around the corner – and it was, because she made it so, whether it was a board meeting, a car trip, or drinking apple cider vinegar.

I think this attitude is one of the things that also made Ms. Glenda one of the strongest women I have ever known – and I come from a line of strong women, so that’s saying something. She was devastated when her husband left her after more than 30 years of marriage – angry, heartbroken, worried about major things like financial stability, but also deeply upset by the disappearance of those little habits developed through living together for so many years, like Dave taking out the trash, putting gas in the car, or bringing her first cup of coffee to her in bed every morning. But she rallied, creating new daily routines and becoming involved in bigger and more exciting professional projects like Young! Tanzsommer (now Stars of Tomorrow), which takes pre-professional companies from the US to Europe to tour and perform each summer. And then, a few years later, when internal politics on the RDA national board led to Glenda being replaced as the director of the Choreography Conference, she pulled herself out of the ashes of that heartbreak – which it was, because she really loved that job – by creating her own Glenda Brown Choreography Project, which provided a forum for her to continue bringing together stellar faculty members to work with young dancers and choreographers. Ms. Glenda was often teased by her business partner Peggy – who was a bit of cynic – about being Pollyanna, the eternal optimist. But it’s that outlook that was the foundation of Glenda being able to move forward after major distress – the sense that better things are out there, that the next adventure is just around the corner.

Ms. Glenda was also compassionate and caring, and if she called you friend that meant something. She was always phoning friends and family members to check up and chat, or to sing Happy Birthday – I still have a voicemail of her singing to me a few years back. She was one of my first calls when my dad died in 1996, and talking to her was like getting a hug over the phone. She told me how sorry she was, how much she knew I loved him, and that it was going to be hard. Her father had been dead for many years at that time, and she told me that she still missed him every day – and she was so right about that grief. She was in Europe when my mom passed away in 2012, but she reached out to let me know she was thinking of me – and later that summer, she pulled me and my boys into her orbit for two weeks at the Glenda Brown Choreography Project to mother and love on us.

This picture was taken there, and Ms. Glenda’s in the middle, pulling off the photo-bomb. She adored my boys, and helped in countless ways to nurture their development as young dancers and young men. When Charles was seven, he told Ms. Glenda that he wanted to go to the Choreography Conference. She told him that he was too young, he had to be 13 to attend as a dancer. He pouted a bit, and she said “I tell you what, come talk to me when you’re 12, and we’ll see what we can do.” We never really talked about it again, but at Festival the year Charles was 12, he asked me to take him to her hotel room because he needed to talk to her. When she answered the door, he said “Ms. Glenda, I’m 12 now. Can I come to the Choreography Conference this year? Remember, you told me to come talk to you when I was 12.” She looked at him seriously, and asked him if he thought he was ready because it was a lot of hard work. Charles, of course, said that he was, and she said “A deal is a deal, so if you think you can handle it, then yes, you can come.” She loved telling that story, and thought it was so funny that he remembered what she had told him at seven and then followed through – but in the actual moment, she treated him like a young professional, which I thought was generous and wonderful. This is how she interacted with all three boys as she provided them various opportunities to study and dance. She also even let Rhys and Walker live with her for the year that they studied at Houston Ballet; they just had to clean up after themselves, take out the trash for her, and guest perform with Allegro Ballet. A few years ago I was chatting with her, and she said “I miss the boys living with me…you know, Rhys would still be up when I’d get home late from the studio, and he’d always eat a fried egg sandwich with me and chat. And it was so nice having them here to take out the damn trash!” She really was a funny lady.

She was also very stylish – although she didn’t spend a ton of money on clothes and didn’t care who knew that. Once, when someone complimented her on her dress, she said “Thank you, I got it for $5 at a garage sale.” But Ms. Glenda also had that special something that made her look great no matter what she was wearing. The same year that Charles first attended the Choreography Conference as a dancer, I was there as a choreographer and my mom and sister brought the twins to visit us. They arrived right before that evening’s showing, and after our initial hugs, I pointed to where Ms. Glenda was so they could go and say hi to her. Walker, seven years old, looked at her and then looked at me and said “Why is she always so fancy?” while moving his hands in little circles by his head. I looked closer – Glenda was wearing shorts, a t-shirt with the neck cut out a la Flashdance, and some flip flops – because it was Texas in July. But her blond curls, the few extra individual false eyelashes she always wore, and her coral lipstick were all there, along with some gold earrings and a necklace. When I told her what Walker had said, Glenda laughed and laughed, and it became another of her favorite stories. It also inspired an impromptu song from the boys and my student Carol several years later while we were on the road to attend the Glenda Brown Choreography Project. We no longer remember all the lines, but here are a couple that we still sing:

Glenda, you are so splenda (sung loudly with emphasis)

She has three eyelashes, only three (whisper-sung with jazz hands, in reference to her false eyelashes; loudly followed by) She’s fancy!

Glenda was absolutely splenda, and her impact in my direction goes even beyond me and the boys. Several of my students were the beneficiaries of her generosity – via scholarships to study, opportunities to teach and choreograph, and knowledge of the dance world. Not to mention that she was such a wonderful example of a life well and fully lived. And we are just one little branch on the Tree of Glenda’s Influence – my timeline on Facebook is flooded with tributes in remembrance – from students, colleagues, long-time friends, traveling companions – each of them with wonderful memories and stories of this fabulous woman.

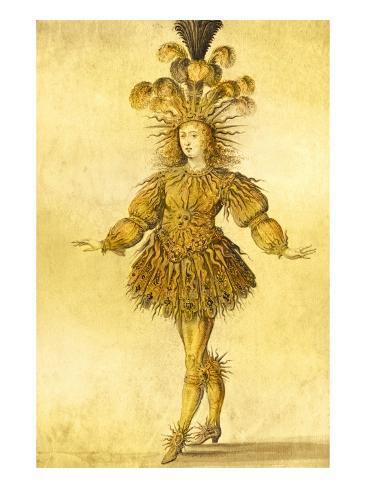

I once gave her a gift that said “Queen of Everything” on it, which became a thing – for a while, everyone gave her something along those lines. But the moniker was so fitting. Her 83+ years were full of all the best that life has to offer – two daughters and then granddaughters she loved with all her heart, a life in dance that fulfilled her, travel to amazing locales all over the world, good food, good wine, good friends, and tequila. And she relished all of it. When a student and her mom gave me a little “Queen of Everything” plaque a few years ago, I said to them “Thanks, but my friend Glenda actually holds that title, and I will never compare.” And that is the truth.

I am heartbroken that she is gone from our world, mad because she had to fight a terrible disease these last few years, and sad that she didn’t make it a little longer so my plans to visit her in June could have come to fruition. But she lives on in the memories of those who knew and loved her, and I know her light will continue to inspire me to try to be caring and generous, to be an optimist and a visionary, to be strong and find ways to rise up when disappointments and heartbreak occur, and to always look for the next adventure around the corner.

Thank you, Ms. Glenda. I love you.